Math and science vocabulary represent more than just words. They represent foundational concepts.

If we don’t teach the language of math and science, students will miss one of the pillars of instruction needed to support their success. Together, we can change that!

The Problem

How students acquire content vocabulary

Content vocabulary terms, sometimes called tier 3 words, are not just specialized terminology. In math and science they often represent foundational concepts. Think about the math and science terms correlation and homeostasis, for example. Each connects to a set of interrelated words or concepts.

- Correlation connects to terms such as positive, negative, coefficient, increase, decrease, strong, and weak. Note that strong and weak mean something very different in the context of correlations than they do in social language.

- With homeostasis, we connect to words such as stimulus, response, feedback, positive, negative, and regulation. Of course in this context, the words positive and negative mean something totally different than they do in the context of correlations. The word regulation also means something totally different in government class, doesn’t it?

- So, context is critical. For this and other reasons, students need to learn the content vocabulary in the math or science classroom—together with the lesson that applies the relevant content knowledge.

Learning vocabulary is not about knowing definitions. Memorizing definitions is an incredibly inefficient way to learn. It tells you nothing about the context. It would be like memorizing the formula for calculating the volume of a cone without knowing what a cone looks like or being aware of any real-world examples of cones.

Mastering new vocabulary—and new concepts—requires six different communication modes: listening, speaking, reading, writing, viewing, and representing. We need to be able to recognize the word when we hear it, differentiate it from similar words, and determine its meaning in the context of the conversation. We need to be able to pronounce it and use it in classroom discourse. We need to be able to decode it in a text passage and understand how it connects to other words. We need to be able to spell it in its many forms, while using it appropriately in a written explanation. We need to be able to recognize visual representations of the word in varied ways, and not be limited to just one concrete example. We need to be able to incorporate it into our own visual representation to demonstrate our knowledge of interrelationships. Only then have we truly mastered the vocabulary.

How students acquire content knowledge

Learning sciences research tells us that building content knowledge generally requires listening to direct instruction, interpreting visual representations, and reading texts. Then learners need to apply the information in classroom discourse, academic writing, and by creating their own visual representations. So, basically, to effectively learn math and science content, you have to learn the language. And that ties back to the same six communication modes needed to learn the vocabulary.

The old instructional model

Unfortunately, this is not what happens in most math and science classrooms. Math and science teachers are not trained in language teaching strategies. They are generally not provided with multimodal, content-based language resources either. And, with so many standards to teach, they don’t have time to figure it out.

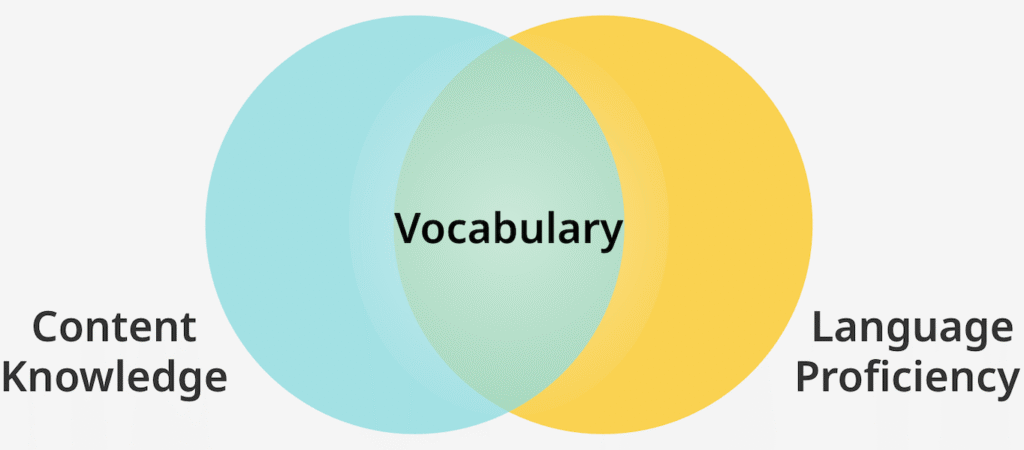

Instead, we tend to fall back on the old model: Teaching the vocabulary. There’s nothing wrong with this! It’s certainly true that vocabulary is a foundation of language proficiency. In fact, in order to comprehend oral and written classroom instruction, a student must know 95% of the words used. So it makes sense to explicitly teach vocabulary.

In this old model, however, we tend to see vocabulary as the only overlap between content and language. We miss the bigger picture! Focusing solely on vocabulary risks missing at least two critical elements:

- Connection to an authentic context.

- Application of the concept to the math and science practices.

The New Model

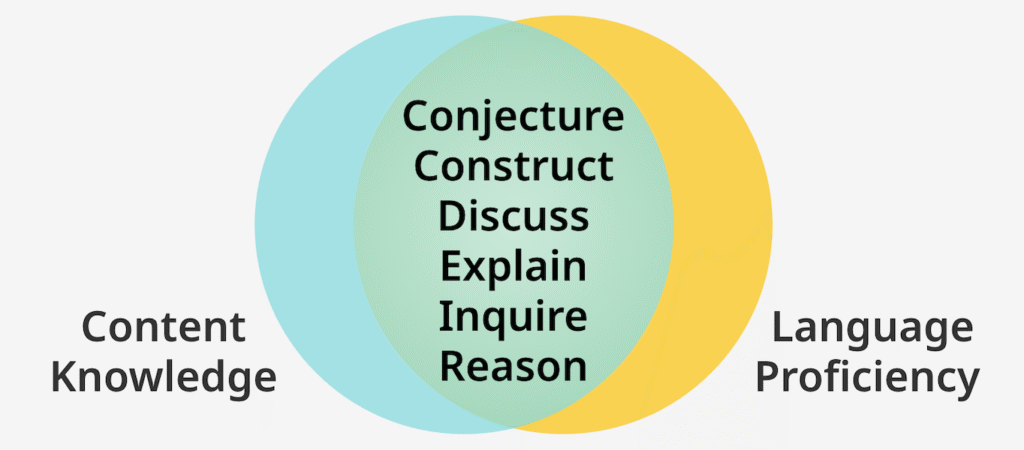

Enter the new model. Learning sciences research shows that the overlap between content and language proficiency is greater than many of us had realized. It goes far beyond vocabulary. Language underpins every one of the math and science practices, from making conjectures and claims to constructing arguments, proofs, and conclusions.

In the new model, students use six communication modes to interact with math and science content. These modes are listening, speaking, reading, writing, viewing, and representing. Here’s why we need all six.

Imagine you are listening to a podcast or having a phone call. Now imagine there’s a bit of background noise or the speaker has an accent that you find difficult to understand. Well, you’re out of luck because you only have an audio channel. A significant percentage of listening comprehension comes through visual channels: lip reading, facial expressions, gestures, and props. As the fidelity of communication drops, so does comprehension.

Now imagine you have access to not one but three interpretive communication modes: listening, viewing, and reading. You see visual aids and text that fill in the gaps in your listening comprehension. This maximizes the fidelity of the communication, does it not? Therefore, it supports more effective learning. This is obvious once you think about it, but this fact is ignored by most curriculum materials, teacher training, and instructional guidance.

The same is true for expressive language: speaking, writing, and representing. Combining these three expressive communication modes is going to improve the fidelity of your students’ communications. Relying on a single mode is going to again reduce the fidelity. Therefore, students will find it easier to demonstrate their full breadth and depth of knowledge if they can speak, write, and represent ideas visually and are not limited to just one of these outlets.

When you layer on learning disabilities, language proficiency, and social and behavioral barriers, you quickly realize that, by ignoring any of the six communication modes, you could really be hindering student learning under the old model. So, how do we transition to the new model? What resources are available to support multimodal content and language integration?

The Content + Language Framework

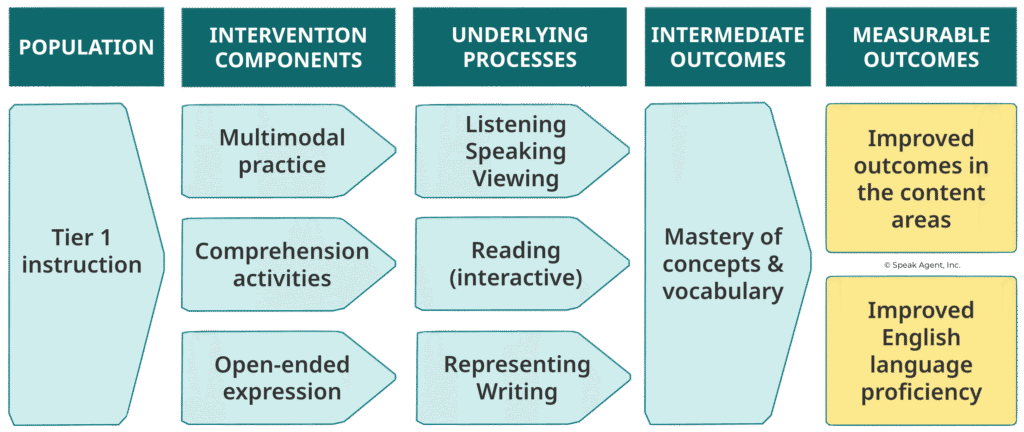

The Content + Language Framework is an approach that closely integrates with the math and science curriculum. It places new concepts and vocabulary in the context of the lesson. The method provides multimodal language development of each concept/word. By multimodal we mean that every word is encountered through listening, speaking, reading, writing, viewing, and representing—all six communication modes. This puts the learner on a path to mastery of the word and underlying concept. We measure progress along this path in three stages:

- Acquire Vocabulary

- Build Comprehension

- Communicate Reasoning

Each stage represents a layer of depth of understanding and proficiency:

- Stage 1 is a measure of a student’s familiarity with new words and concepts through repeated multimodal (aural, textual, verbal, and visual) exposures. This occurs in the Acquire Vocabulary stage of each digital lesson in Speak Agent, with practice listening, decoding, and rearranging word parts, for example. Research shows that 8 to 10 exposures are needed to acquire familiarity with new vocabulary and concepts, and roughly double that for multilingual learners.

- Stage 2 is a measure of a student’s understanding of a new term in different contexts. This occurs in the Build Comprehension stage of each digital lesson in Speak Agent. Students engage in reading and manipulating text passages and visual representations across a variety of contexts and communication modes. This variety is helpful for understanding the nuances of how word forms and meaning can change in different contexts. Students use strategies such as sentence frames and stems or rearranging sentence parts, with built-in learning supports and scaffolds. They also make connections to background knowledge and previously mastered concepts.

- Stage 3 is a measure of a student’s usage of a concept in expressive language to communicate their reasoning and content knowledge. In the Communicate Reasoning stage in Speak Agent, students use expressive language (writing/editing, speaking, and representing) to apply their knowledge. This stage offers opportunities for open-ended self-expression, building fluency while deepening concept knowledge and reinforcing learning loops such as math modeling or Claim, Evidence, Reasoning (CER).

You will find these three stages noted in various reports throughout Speak Agent at the school, class, and student levels. They may be shortened to Acquire > Build > Communicate. Learn more in our data monitoring guides:

Logic Model

Connections to the Math Practices

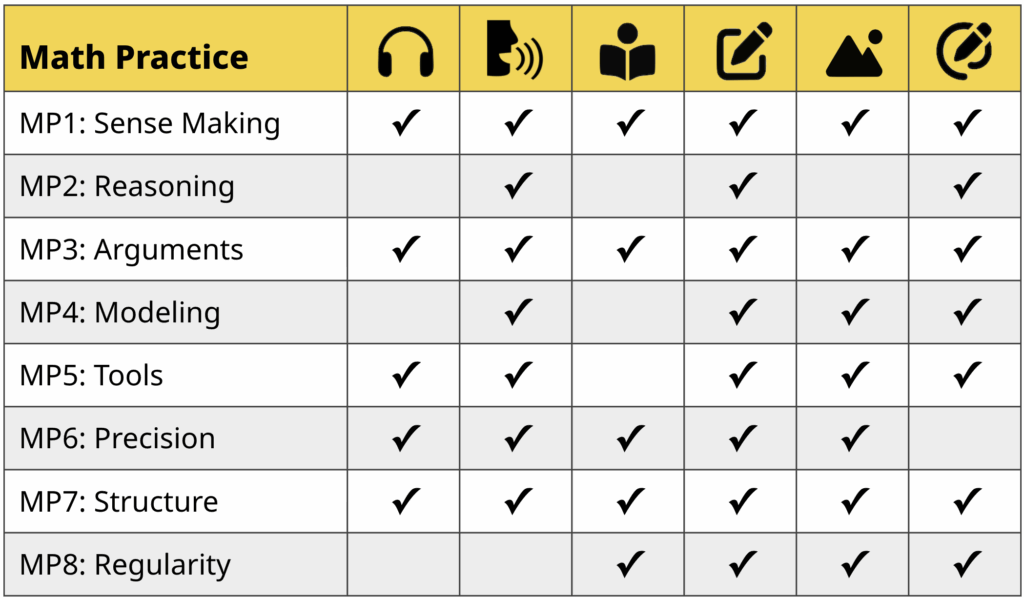

The table below shows our analysis of how proficiency in the six domains of language connects to the Standards for Mathematical Practice.

What do the table icons mean?

Listening. Interpreting direct instruction, discourse, and other auditory input.

Speaking. Classroom discourse and practice using content-based language.

Reading. Encourages use of context clues and reflection to respond to C.R.O.W.D. prompts, often including tools to manipulate or complete the text.

Writing. Explanations, descriptions, and responses to C.R.O.W.D. prompts.

Viewing. Visual learning where students interpret meaning from images, charts, graphs, diagrams, animations, videos, or other graphical elements.

Representing. A form of expression where students communicate using visuals they create or layer upon and annotate.

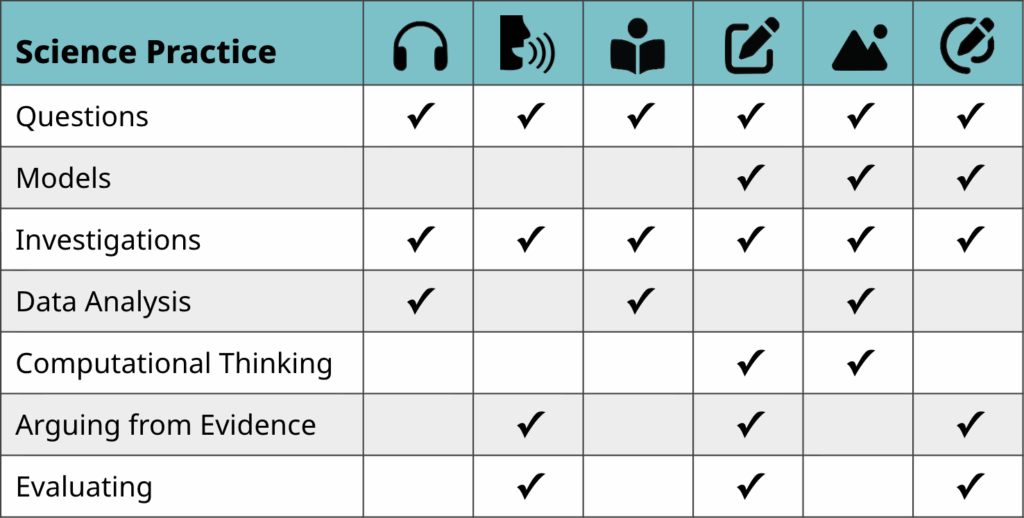

Connections to the Science and Engineering Practices

The table below shows which of the communication modes support each of the Science and Engineering Practices (SEPs) in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).

What do the table icons mean?

Listening. Interpreting direct instruction, discourse, and other auditory input.

Speaking. Classroom discourse and practice using content-based language.

Reading. Encourages use of context clues and reflection to respond to C.R.O.W.D. prompts, often including tools to manipulate or complete the text.

Writing. Explanations, descriptions, and responses to C.R.O.W.D. prompts.

Viewing. Visual learning where students interpret meaning from images, charts, graphs, diagrams, animations, videos, or other graphical elements.

Representing. A form of expression where students communicate using visuals they create or layer upon and annotate.

Putting It into Practice

Next, learn how to put the theory into practice in your classroom.

References

The Content + Language approach was inspired by these learning sciences research papers:

Bravo, M.A., Cervetti, G.N., Hiebert, E.H., Pearson, P. D. (2007). From passive to active control of science vocabulary. In D.W. Rowe et al. (Eds.), 56th Yearbook of the National Reading Conference. Oak Creek, WI: National Reading Conference.

Hakuta, K (2013). ELLs and CCSS. Institute on Assessment in the ERA of the Common Core, International Reading Association, April 19, 2013, San Antonio, TX.

Laufer, B., Ravenhorst-Kalovski, G. (2010). Lexical threshold revisited: Lexical text coverage, learners’ vocabulary size and reading comprehension. Reading in a Foreign Language, April 2010, Volume 22, No. 1, pp. 15–30.

Peregoy, S. F., & Boyle, O. (2013). Reading, Writing, and Learning in ESL: A Resource Book for Teaching K-12 English Learners, 6th Edition (pp. 224-248). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Snyder, E., Witmer, S. E., & Schmitt, H. (2017). English language learners and reading instruction: A review of the literature. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 61(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2016.1219301

Zahner, W., Calleros, E.D. & Pelaez, K. (2021). Designing learning environments to promote academic literacy in mathematics in multilingual secondary mathematics classrooms. ZDM Mathematics Education 53, 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-021-01239-0